In the world of international logistics, understanding how weight is calculated and billed is not just helpful—it’s essential. This shipping weight guide provides a comprehensive look at how different weight types affect freight rates, transport planning, and compliance requirements. Whether you’re managing eCommerce parcels or full container loads, the right approach to weight estimation can protect your bottom line. Let’s explore how to optimize shipping performance through smarter weight management.

Why Shipping Weight Matters

In the world of logistics and freight forwarding, understanding shipping weight is not just a technical requirement—it’s a critical component of cost control, transportation planning, and supply chain efficiency. This comprehensive shipping weight guide outlines why it deserves your full attention.

Shipping weight impacts everything from the selection of transport modes to the calculation of freight rates and even customs duties. Whether you’re managing air freight, ocean cargo, or last-mile courier delivery, how you calculate and report weight can significantly influence both operational costs and compliance outcomes.

Below are some of the key reasons why shipping weight matters:

- Direct impact on transportation costs: Most carriers, especially air and courier services, charge based on weight or dimensional weight. The heavier or bulkier your cargo, the higher your shipping bill.

- Determines the choice of transport mode: Lightweight but high-value goods are often shipped by air, while heavy, dense cargo is better suited to sea or rail freight due to cost efficiency.

- Critical for vehicle and container load planning: Misjudging shipping weight can result in container overloading, vehicle safety issues, or even regulatory penalties.

- Essential for customs declarations and compliance: Incorrect weight declarations can lead to clearance delays, fines, or goods being held at borders.

- Supply chain optimization: Weight affects not only freight costs but also inventory planning, pallet configuration, and warehouse handling procedures.

Core Categories of Shipping Weight & Calculation Methods

Shipping weight is not a one-size-fits-all concept. Depending on the purpose and transport method, several weight classifications are used by carriers, freight forwarders, and customs authorities. Each plays a different role in pricing, load planning, and compliance. Below are the core categories of shipping weight along with how they are calculated and applied in real-world shipping operations.

Gross Weight

Gross weight refers to the total weight of the shipment, including the product, its packaging, and any pallets, crates, or containers used for transportation. It is the most commonly referenced weight when calculating freight charges and checking equipment limits.

In container shipping, gross weight is vital to ensure the total cargo (including container tare) does not exceed the Maximum Gross Weight defined by the container’s structural rating. For instance, a 20-foot general-purpose container typically supports a max gross weight of around 30,480 kg.

Gross weight is also the primary figure used on transport documents like the bill of lading (B/L) and air waybill (AWB), where exceeding equipment or aircraft limits can lead to rebooking, surcharges, or outright cargo rejection.

Net Weight

Net weight is the weight of the goods themselves, excluding any form of packaging, dunnage, pallets, or transport containers. It reflects the actual quantity of commodity being traded and is a critical figure in commercial transactions.

This value is essential for:

- Commercial invoices and packing lists

- Customs declarations, particularly in countries where duty is calculated based on net weight

- Inventory and procurement systems, especially in bulk or industrial commodities

In international trade contracts (FOB, CIF,..), net weight may be the basis for pricing, especially when dealing with raw materials, grains, or chemicals. It’s also the preferred unit in Certificates of Origin (CO) and Phytosanitary Certificates, which often exclude transport packaging.

Tare Weight

Tare weight refers to the weight of the container, pallet, or packaging alone, with no product content included. It plays a critical role in accurately calculating net and gross weight values.

Typical examples of tare weight include:

- Wooden pallet: ~15 – 20 kg

- Plastic drum: ~5 – 8 kg

- 20’ steel shipping container: ~2200 – 2300 kg

In trucking operations, tare weight is used during weighbridge measurements. When a loaded truck is weighed and then emptied, the tare is subtracted to calculate the net payload:

Net = Gross (loaded weight) − Tare (vehicle or container)

Tare weight is especially important in containerized cargo, as exceeding net payload limits can breach axle load laws or cause handling difficulties at terminals.

Additionally, tare weight must be declared when complying with SOLAS Verified Gross Mass (VGM) regulations for ocean freight, where shippers are responsible for declaring the accurate gross weight (including container tare) before gate-in.

Volumetric / Dimensional Weight

Volumetric or dimensional weight is used primarily in air freight and courier services. Since space is often more limited than weight capacity, carriers charge based on the higher of actual weight or dimensional weight.

This calculation aims to account for light but bulky shipments that occupy a disproportionate amount of space.

Standard air freight formula:

- Dimensional weight (kg) = (Length × Width × Height in cm) / 6000

Example:

- A box measuring 100 × 50 × 40 cm has a volumetric weight of (100×50×40)/6000 = 33.3 kg

- If the actual weight is only 15 kg, you will still be charged based on 33.3 kg

This illustrates why understanding volumetric weight is essential when shipping large but lightweight cargo.

Chargeable Weight

Chargeable weight is the greater of the actual weight and volumetric weight. It is the definitive value that determines your shipping cost. Carriers, especially in air freight and express courier services, use this model to maximize space utilization and balance cost recovery.

In practice, if a shipment is heavy but compact, the actual weight is used. If it is light but bulky, dimensional weight becomes the chargeable weight. This approach incentivizes shippers to use packaging that is both protective and space-efficient.

Example:

- Box A: 10 kg actual weight, 18 kg volumetric weight → charged as 18 kg.

- Box B: 25 kg actual weight, 15 kg volumetric weight → charged as 25 kg.

Billable Weight

Billable weight is closely related to chargeable weight but reflects the final invoiced weight after carriers apply internal policies such as minimum chargeable weights, rounding rules, or zone surcharges.

For example, many couriers set a minimum billable weight of 0.5 kg even for very small packages. Additionally, weight is often rounded up to the nearest 0.5 or 1 kg. Thus, a package with 4.2 kg chargeable weight may be billed at 4.5 kg.

It is crucial to review the terms and conditions of your logistics provider, as the billable weight can influence not just cost but also claims and SLA performance. Discrepancies between chargeable and billable weights should be monitored regularly, especially in large-volume contracts where small overcharges can accumulate significantly.

Payload Weight

Payload weight refers to the actual cargo weight carried by a vehicle, trailer, or container, excluding the tare (empty weight of the transport unit itself). This figure is essential in planning for road freight and heavy haul operations.

For instance, if a flatbed truck has a Gross Vehicle Weight Rating (GVWR) of 10,000 kg and its tare weight is 6,000 kg, the payload capacity is 4,000 kg. Exceeding this limit can lead to vehicle wear, road safety violations, or even fines during roadside inspections.

Accurate payload calculation is also critical when applying for overweight permits, organizing multiple deliveries, or optimizing delivery routes to avoid toll surcharges or restricted roads. Some shippers mistakenly overlook components like fuel, driver, and auxiliary equipment when calculating payload, which can lead to unexpected overloading.

Deadweight Tonnage (DWT)

Deadweight Tonnage (DWT) is a crucial measurement used primarily in ocean freight to define the maximum weight a vessel can safely carry. This includes not only cargo but also fuel, crew, provisions, freshwater, and all other operational necessities.

Unlike gross tonnage, which relates to the internal volume of the ship, DWT reflects the vessel’s carrying capacity in metric tons (1,000 kg). It is calculated as the difference between a ship’s displacement when fully loaded and its lightweight (displacement when empty).

For example:

- A vessel with a DWT of 50,000 MT can carry a combination of cargo, fuel, and supplies up to that total weight.

DWT is a key specification in charter party agreements, freight rate negotiations, and port operations. Misjudging DWT capacity can lead to overdraft risks, port access restrictions, or excessive fuel consumption.

Container Max Gross

The “Container Max Gross” weight refers to the maximum allowable combined weight of the shipping container and its contents, as defined by ISO standards and enforced by carriers and terminal operators. Each container has a clearly marked max gross limit, typically found on its CSC plate. Common values include:

- 20-foot GP container: Max Gross ~30,480 kg

- 40-foot GP container: Max Gross ~32,500 kg

- 40-foot High Cube: Often matches or slightly exceeds 32,500 kg

This total includes:

- The container’s own tare weight (e.g., ~2,200–2,400 kg)

- The payload (goods + packaging)

Exceeding the Max Gross can lead to:

- Cargo rejections at port terminals

- Fines for overweight containers during inland transport

- Safety risks during crane operations or vessel loading

Freight forwarders and exporters must always cross-check booking confirmations and local road weight regulations before stuffing cargo. Some carriers or countries may also impose lower limits than the container’s structural capacity, based on axle load laws or national transport rules.

Shipping Weight by Mode of Transport

Shipping weight plays a different role depending on the mode of transportation used. Each transport type – air, sea, road, and courier – has its own regulations, constraints, and pricing models. Understanding these distinctions is vital for shippers to calculate accurate costs, select the right carriers, and maintain legal compliance.

Air Freight

Air freight is highly sensitive to both actual and dimensional weight due to the limited space and high cost per kilogram. In most cases, air carriers use the volumetric weight formula (L×W×H in cm / 6000) and compare it against the actual weight. The greater of the two becomes the chargeable weight.

Key considerations:

- Chargeable weight is the billing standard.

- Weight breaks exist in rate sheets (e.g., 45 kg, 100 kg, 300 kg tiers).

- ULDs (Unit Load Devices) and aircraft belly limitations require weight balancing.

Exceeding certain weight thresholds may result in cargo needing rebooking on freighter aircraft or incurring additional handling fees. Freight forwarders often pre-check volumetric ratios before quoting to prevent surprises.

Sea Freight (FCL/LCL)

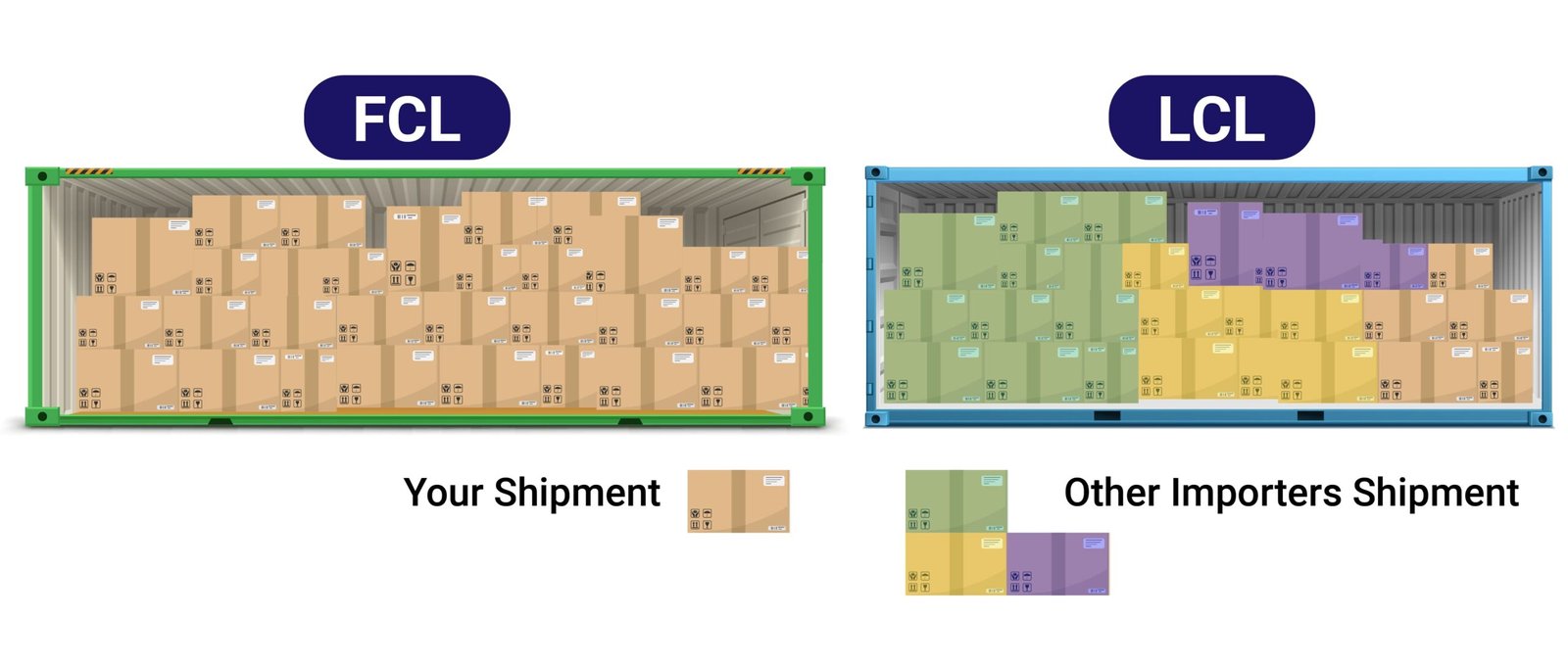

For ocean freight, shipping weight impacts both container utilization and vessel stowage planning. There are two main types of bookings:

- FCL (Full Container Load): Shipper is responsible for ensuring the gross weight (cargo + container) does not exceed the container’s Max Gross. Inaccurate declarations can lead to rejection at the port or overloading penalties.

- LCL (Less than Container Load): Freight is consolidated with other cargo. Charges are based on W/M (Weight or Measurement)—you’re billed per 1 ton or per 1 cubic meter, whichever is greater.

The shipping weight guide is especially useful here as LCL billing can become complex when cargo volume and mass do not align proportionally.

Important notes:

- SOLAS VGM mandates shippers declare Verified Gross Mass before loading.

- Port handling equipment has weight limits. Overloading causes delays.

- DWT (Deadweight Tonnage) limits determine how much cargo a vessel can carry without breaching draft regulations.

Road Freight

In trucking operations, payload weight is crucial for route planning, legal compliance, and fuel efficiency. Each truck has a GVWR (Gross Vehicle Weight Rating), which includes the vehicle’s tare weight and its maximum allowable cargo.

Key practices:

- Overloading violates axle weight limits, leading to fines or vehicle seizure.

- Weighbridges at checkpoints monitor gross and axle loads.

- High payloads increase fuel consumption and reduce vehicle lifespan.

In cross-border road freight, weight allowances vary by country, requiring logistics managers to validate compliance with both origin and destination regulations.

Courier / Express

In courier services ( DHL, FedEx, UPS,…), dimensional weight nearly always determines pricing. Small but bulky items often cost more than heavier but compact shipments.

Features to consider:

- Dimensional formula: L×W×H in cm / 5000 or 4000, depending on the carrier.

- Minimum billable weight applies (often 0.5 kg).

- Surcharges may apply to packages above certain thresholds (e.g., 30 kg or 120 cm in length).

Couriers use automated dimension scanners at sortation hubs, so accuracy in declaring size and weight protects against unexpected invoice adjustments.

Frequent Errors in Shipping Weight Estimation

Even experienced shippers can make costly mistakes when calculating shipping weight. These errors not only inflate logistics costs but can also result in shipment delays, safety risks, or regulatory violations. Below are the most common pitfalls to watch for:

Ignoring packaging and packing materials

One of the most frequent oversights is calculating weight based solely on the product itself, without accounting for external packaging, inner cartons, pallets, or crates. This leads to an underestimation of gross weight, which can result in:

- Underpayment of freight charges (followed by billing adjustments)

- Breaching container or vehicle max gross limits

- Errors in customs declarations or insurance valuations

Shippers should always conduct pre-shipment weigh-ins of fully packed cargo to confirm final gross weight.

Using only product weight

Similar to ignoring packaging, using product weight alone can distort logistics planning. In LCL shipping, for example, the consolidated freight forwarder needs to know the total cubic meter and weight of the packed unit, not just the internal item. Also, e-commerce sellers often publish net weight for catalog purposes, but this is insufficient for courier or air freight shipping where chargeable weight is the pricing standard.

Confusing actual weight vs. chargeable weight

Many first-time shippers misunderstand the difference between actual (gross) weight and chargeable weight. This leads to discrepancies between estimated and final shipping costs-especially in air and courier transport.

For example:

- A product that weighs 8 kg but is bulky enough to be charged at 14 kg volumetric weight will result in higher-than-expected invoices if only the actual weight was considered during quoting.

Understanding the correct dimensional formulas per transport mode and applying them accurately is key to cost predictability.

Overloading vehicles beyond limits

In road freight and container shipping, failing to comply with payload and Max Gross limits can have serious consequences:

- Legal fines or detentions at weighbridges

- Vehicle wear and reduced fuel efficiency

- Safety hazards for drivers and surrounding traffic

Shippers must be aware of country-specific axle weight laws, especially for cross-border transport, and avoid loading beyond equipment ratings.

Applying the wrong volumetric formula per transport mode

Each carrier and mode of transport may use a different volumetric divisor (5000, 6000, or 4000). Applying the wrong formula can lead to misquoted chargeable weights.

For instance:

- Air freight: (L×W×H) / 6000

- Courier: (L×W×H) / 5000 or 4000 depending on the provider

Ensure alignment with carrier-specific rules and confirm whether dimensions are measured in centimeters or inches. Errors here can snowball across hundreds of shipments.

Cost Implications of Shipping Weight

Shipping weight doesn’t just impact how goods are handled—it directly shapes how much you pay. Understanding the cost structure tied to weight across transport modes helps logistics managers budget more accurately and negotiate better rates.

Air Freight

In air freight, chargeable weight is king. Most air carriers calculate charges using the greater of actual weight or volumetric weight (typically using the divisor 6000).

Key cost factors:

- Weight break tiers: 45 kg, 100 kg, 300 kg, etc.

- Fuel surcharges and security fees are calculated based on chargeable weight.

- Airlines also apply Minimum Charges for very light shipments.

A shipment that’s light but occupies substantial space can double or triple expected airfreight charges if not packed efficiently.

Ocean Freight (LCL)

In Less-than-Container Load (LCL) ocean freight, pricing is typically based on W/M (Weight or Measure). You are charged per revenue ton:

- 1 metric ton (1000 kg) or 1 cubic meter (CBM)—whichever is greater.

Cost implications:

- If your cargo is 600 kg but occupies 2.5 CBM, you are charged for 2.5 revenue tons.

- Densely packed goods can reduce CBM and save costs.

- Port charges and documentation fees often scale with the number of CBMs.

Properly optimizing cargo density can reduce freight spend in LCL shipments.

Road Freight

Road freight pricing varies by region and shipment type (FTL vs LTL), but weight still plays a major role:

- LTL (Less-than-Truckload): Priced based on weight slabs and freight class.

- FTL (Full Truckload): Limited by payload and axle weight constraints.

Exceeding payload limits may lead to:

- Overweight fines.

- Higher fuel consumption and wear.

- Need for special permits or escort services.

Consolidating multiple lightweight shipments into denser loads can reduce per-unit costs.

Courier / Express

In courier and parcel networks, the dimensional weight is the dominant pricing factor.

Major carriers like FedEx, UPS, and DHL use their own volumetric formulas and apply additional fees:

- Large Package Surcharge.

- Overweight Surcharge (often 30+ kg).

- Remote Area or Extended Delivery surcharges.

Even a minor packaging change can shift a parcel into a higher billing bracket. Optimizing box sizes for cubic efficiency is critical in e-commerce logistics.

Pricing Thresholds

Across all modes, specific pricing thresholds influence freight rates. Knowing these can help you plan smarter:

- Minimum chargeable weight: Some carriers apply flat rates for shipments below 20 or 45 kg.

- Tiered rates: Per-kg rates drop as weight increases.

- Surcharges: Apply above defined limits (e.g., >120 cm in length or >70 kg gross).

- Consolidation incentives: Freight forwarders offer discounts on larger, bundled shipments.

By understanding how weight influences freight pricing, businesses can minimize logistics costs through better packing, smarter routing, and well-informed transport mode selection.

Shipping weight may seem straightforward, but it influences nearly every aspect of freight operations-from cost efficiency to regulatory compliance. With this detailed shipping weight guide, businesses gain the knowledge needed to avoid costly mistakes and improve logistics accuracy. By understanding key concepts like gross, chargeable, and volumetric weight, you can make informed decisions across all transport modes. Mastering shipping weight is a crucial step toward building a smarter, more resilient supply chain.

Ready to turn insights from this shipping weight guide into real logistics results? Keys Logistics delivers advanced WMS, TMS, and fulfillment solutions tailored for growth. We integrate directly with platforms like Shopify, Amazon, and TikTok Shop to streamline your operations. With a global carrier network and real-time visibility, we ensure faster, smarter, and more reliable delivery. Contact us today to scale your shipping with confidence—backed by logistics expertise and innovation.

Tiếng Việt

Tiếng Việt 中文 (中国)

中文 (中国)